HTMX, Functional Composition, and the SEO Problem

Building web pages that work for both users and crawlers

Date:- htmxwebarchitecturebackend

When I taked the desition of building this blog using HTMX, I ran into an interesting architectural challenge. A problem that seems simple in the surface, but quickly reveals itself to the way how you structure your entire application.

One of the main chalenges is the problem of having the same URL work for both direct visits (from search engines, bookmarks, shared links) and internal navigation via HTMX.

The Dilemma

HTMX has the aproach of extend the clasical web in a way that lets you make HTTP requests directly from the HTML elements and swap parts of the DOM with the server's response with very litle mental overhead

But this simplicity comes with a design question: when someone clicks a link via HTMX, you want to send just the content fragment. When a crawler or user arrives directly at that same URL, they need the complete HTML document with navigation, styles, scripts—everything.

You could solve this with separate endpoints, but that means maintaining two versions of every route, and every line of code is a liability to mantain.

Visualizing Pages as Nested Structures, a Functional Composition Approach

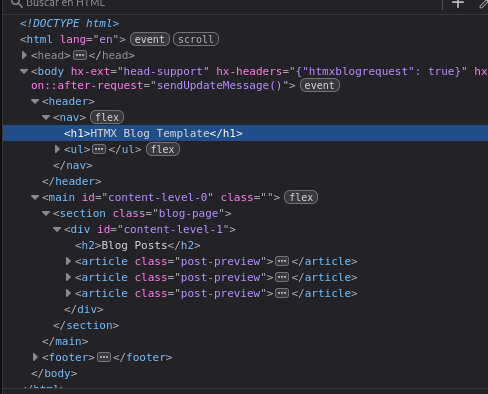

Here's two key insights: the first is that web pages are nested structures. Your content sits inside a section, which sits inside the body, which sits inside the HTML document. Something like:

plaintext

HTML Document → Body → Section → Article Content

When you navigate within your site, most of this structure stays the same. Only the innermost content changes. That's why single-page applications feel fast—they're not re-rendering everything.

The second insight is that HTMX is that allow us to send the inner content only

Joining this aproachs, gives us the same benefit of the single page aplications, but with a crucial difference, where is not the client side code meidiating thorought inner rooting logic or state managment the contet, but is the server that just sends the content.

When we see the nesting, we can treat each level of the page structure as a composable function. Each function takes the next level's content as input and wraps it in the appropriate HTML.

javascript

function body(content) {

return `

<html>

<head>...</head>

<body>

<nav>...</nav>

<div id='content-slot'>

${content}

</div>

<footer>...</footer>

</body>

</html>

`;

}

function blogSection(content) {

return `

<section class='blog'>

<h1>Blog</h1>

<div id='post-slot'>

${content}

</div>

</section>

`;

}

function article() {

return `<article>Hello World!</article>`;

}Now you can compose these functions to build complete pages:

javascript

// Full page for external requests

body(blogSection(article()))

// Just the fragment for HTMX requests

article()Detecting the Request Type

To know which response to send, we need to distinguish between external and internal requests. HTMX makes this easy with custom headers. You can add a header to all HTMX requests:

html

<body hx-headers='{"X-Requested-With": "htmx"}'>

<!-- All HTMX requests from here will include this header -->

</body>Then on the server:

javascript

app.get('/blog/my-post', (req, res) => {

const content = article();

if (req.headers['x-requested-with'] === 'htmx') {

// Internal navigation - send just the fragment

return res.send(content);

}

// External request - send the full page

res.send(body(blogSection(content)));

});The Real-World Implementation

In this blog, I use a PageFragment object to represent each level. It contains the HTML body,

metadata, styles—everything needed for that piece of the page. Then I have wrapper functions

that compose these fragments together.

When Express handles a route, it checks for the custom header headers['calaverd-blog']

1

and either returns the fragment directly or wraps it in the full page template.

The beauty is that routes are generated automatically from a tree structure, and each route knows how to compose itself:

javascript

// The site structure as a tree

const siteMap = {

fragmentFunction: rootContent,

children: {

'en': {

fragmentFunction: mainPage,

children: {

'blog': {

fragmentFunction: blogPage,

children: {

'my-post': {

fragmentFunction: postContent,

children: {}

}

}

}

}

}

}

};

// Routes are built recursively

function constructSite(map, route='/', fragmentFunctions=[]) {

const allFunctions = [...fragmentFunctions, map.fragmentFunction];

app.get(route, (req, res) => {

if (req.headers['calaverd-blog']) {

// Internal HTMX request - send just this fragment

return res.send(map.fragmentFunction(null).bundle);

}

// External request - compose all functions from root to here

const fullPage = allFunctions.reduceRight(

(fragment, fun) => fun(fragment),

new PageFragment

);

res.send(fullPage.body);

});

// Recursively build child routes

Object.entries(map.children).forEach(

([path, child]) => constructSite(child, route + path, allFunctions)

);

}What This Gets You

This architecture gives you several things for free:

- SEO that just works - Crawlers get complete HTML documents

- Fast navigation - Users only get served the iner content that changed

- Shareable URLs - Every URL works as a direct link

- Single source of truth - One route, one composition function

- No hydration issues - The server already knows what to send

Al this thanks to a set of functions and composing HTML strings, simple and undestable code.

The Tradeoffs

For content-focused sites with some interactivity, this functional composition pattern with HTMX is remarkably powerful. You get the development simplicity of traditional server-side rendering with the UX smoothness of a single-page app.

Of course, no size fits all, this does is not a magic bullet for all use case. If you need complex client-side state, real-time collaboration, or offline functionality, you're going to need to use a JavaScript framework to support those features.

The whole system emerges from simple parts that compose together. Each function does one thing. The complexity you see is the complexity that's actually there.

The Link Helper

To avoid manually entering HTMX attributes on every link, I use a helper function that sets the appropriate target based on URL depth:

javascript

function link(url, text) {

const levelNumber = Math.max(

[...url].filter(c => c === '/').length - 1,

0

);

return `<a href="${url}"

hx-get="${url}"

hx-target="#content-level-${levelNumber}"

hx-swap="innerHTML show:top swap:300ms"

hx-push-url="true">${text}</a>`;

}The content-level IDs are defined in the templates themselves when creating the page structure.

The PageFragment Class

Each piece of content is represented by a PageFragment object:

javascript

class PageFragment {

constructor() {

this.title = '';

this.description = '';

this.body = '';

this.styles = '';

this.lang = 'en';

this.keywords = [];

}

get bundle() {

return `

<head hx-head="re-eval">

<title>${this.title</title>

<meta name="description" content="${this.description}">

</head>

${this.body}

`;

}

}The bundle getter wraps the content with <head> tags marked hx-head="re-eval".

HTMX's head-support extension uses this to update the page title during navigation.

Tradeoffs

What Works

- SEO - Complete HTML for crawlers

- Debugging - Check the Network tab, see what the server sends

- No build step - Pure ES modules

- Fast - Server sends complete HTML, no hydration wait

- Small - ~14kb HTMX vs 200kb+ for typical React SPAs

The Downsides

- Manual routes - Each page added to the site map by hand

- Template literals - No syntax highlighting without editor plugins

- Doesn't scale well - Deep nesting gets messy

Try It Yourself

If you're building a blog, documentation site, or content-heavy application, this pattern might work for you. Start with pages as composable functions and see where it goes.

I've created a simplified example repository that demonstrates the core architecture: htmx_minimalist_blog_example 2

The example strips away bilingual support, file-based content, and other production features to focus on the architectural pattern.